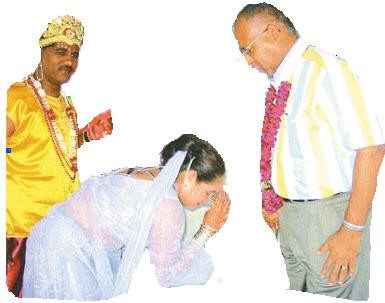

Devotees

This is a draft copy of my paper.

Please make corrections and comments to me personally.

mahab@tstt.net.tt

Kumar

ABSTRACT OF PAPER

CONFERENCE ON HUMAN RIGHTS EXPERIENCES:

PEOPLE OF INDIAN ORIGIN IN THE CARIBBEAN

ORGANISED BY

GLOBAL ORGANIZATION OF PEOPLE OF

INDIAN ORIGIN (GOPIO)

&

THE GUYANESE EAST INDIAN

CIVIC ASSOCIATION (GEICA)

AT

ST JOHN'S UNIVERSITY, JAMAICA, NEW

YORK

SATURDAY MARCH 20, 2004

DR KUMAR MAHABIR -

ANTHROPOLOGIST

DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATIONS, COSTAATT (COMMUNITY COLLEGE)

MT HOPE MEDICAL SCIENCES COMPLEX

TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO

POLICE ASSAULT OF PEOPLE

PROTESTING AGAINST CRIME:

THE OCTOBER 6, 2003 ARRESTS

IN TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO

The Prime Minister of Trinidad & Tobago (right) commonly known as the Engineer of Kidnappings. He placed his island 2nd in the WORLD for KIDNAPPINGS

Abstract

- On October 6th 2003, disgruntled people in a village in multi-ethnic Trinidad

began a peaceful procession that started with an inter-faith service. The men,

women and children were escorted by three policemen and were led by the Mayor of

Chaguanas. During the course of the two-mile journey to the town, the throng

swelled to 1,000 participants. Businesspeople had also closed their stores in

order to join the march against the Government's apparent inability to deal with

the wild wave of crime and kidnappings directly mainly towards Indians. On

reaching the town, heavily-armed African policemen confronted the crowd and

refused them permission to enter a car park to hold a public meeting. A heated

debate ensued which erupted into police assault and the arrests of nine people

including an imam, a pandit, two politicians and an investigative journalist.

Using mainly newspaper reports and eyewitnesses' accounts, this paper seeks to

describe and analyze the police action against the anti-crime march in Chaguanas

from the perspective of human rights violation and racial discrimination. It is

argued that the aggression unleashed to the protesters by the police is a

violation of people's right to dissent peacefully. Article 1 of the UN Charter

and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 states that discrimination

on the ground of race, colour or ethnic origin is an offence to human dignity,

and is a violation of the human rights and fundamental freedoms of a people.

Keywords - human rights

violation; crime; racial and ethnic discrimination, Trinidad.

Correspondence - Dr Kumar Mahabir,

President, Association of Caribbean Anthropologists,

Swami Avenue, Don Miguel Road, San Juan, Trinidad and Tobago, West Indies.

Tel: (868) 675-7707. Tel/fax: (868) 674-6008. Cellular:

(868) 756-4961

E-mail: mahab@tstt.net.tt

INTRODUCTION

Trinidad and Tobago is a twin-island democratic republic located in the southern

Caribbean 11 kilometers (7 miles) from Venezuela. It is a wealthy country

which exports petroleum and natural gas to the U.S. and Europe from its

southern-based industrial complexes. It is a base for the world's energy giants

like BP Amoco, British Gas, EOG, BHP Billiton, and Exxon Mobil. Canadian

companies in the island include PetroCanada, Talisman Energy, Vermilion Oil and

Gas, and Methanex - the world's largest methanol company.

Trinidad and Tobago has a population of 1.3 million consisting mainly of people

of African and (East) Indian origin who are almost equal in number. They are

descendants of slaves and indentured labourers who were brought to work in the

sugarcane plantations in the eighteenth and nineteenth century under British

colonial rule. Most Indians are either Hindus (24%), Muslims (6%) or

Presbyterians (3%), though conversion to Christian evangelical faiths has been

increasing dramatically over the years. Roman Catholics form the largest (29%)

religious group in the society.

Electoral politics in the islands have always been divided sharply along ethnic

lines with the majority of Indians now supporting the Opposition UNC, and

Africans rallying behind the ruling PNM. Africans dominate the PNM Government,

the security force and the civil service. Indians are to be found mainly in

middle and lower rungs of the service, retail businesses, private industries and

agriculture. Ethnic tension in Trinidad is such a serious issue that the Prime

Minister deemed it necessary to establish a Race Relations Committee, and the

President appointed a National Self-Discovery Committee in 2003.

Writing in the Ottawa Citizen of January 24, 2004 in an article investigating

"Trinidad's ties to terror," journalist Donna Jacobs states that the

island's "tropical beauty conceals a darker identity." Associated

Press reporter Michael Smith (March 30, 2003) also writes that "Trinidad is

a study of extremes," with it ostentatious wealth flourishing next to

severe poverty, and exotic restaurants not far from smoking garbage dumps. It is

a place of colour and music, he states, where "people lose lives and loves

in almost daily shootings and kidnappings."

HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS

International Human Rights Day is usually observed world-wide on December 10.

The Day is of special importance to Trinidad because of the multiracial,

multi-cultural and multi-ethnic nature of the society. In Trinidad and the wider

Caribbean, the issues featured include prison conditions, death sentence, police

abuse, domestic violence, and the rights of women. Never is the issue of racial

discrimination against ethnic minorities and Indians discussed.

Trinidad has signed and ratified the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of

1948, and if Indians are not treated equally as other citizens by the

Afro-dominated Government, then the state is guilty of non-compliance. Article 1

reaffirms the principles of equal treatment:

Discrimination between human beings on the ground of race, colour, or ethnic

origin is an offence to human dignity and shall be condemned as a denial of the

principles of the Charter of the United Nations, [and] as a violation of the

human rights and fundamental freedoms proclaimed in the Universal Declaration of

Human Rights ..

The UN views racial discrimination as morally wrong, fundamentally unjust, and

an evil which must to be eradiated. It declares racism (direct, indirect, covert

or overt) as totally abhorrent to the conscience and dignity of mankind, and a

crime against humanity. Discrimination, and unfair or arbitrary distinctions,

have no part to play in a decent society, and an "accident of birth,"

such as race, ethnicity, or gender should not be a liability. Unequal treatment

based on race, colour or ethnic origin is so much a serious concern for the UN

that it held a World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination,

Xenophobia and Related Intolerance in South Africa in 2001. What is needed in

Trinidad and Guyana is the establishment of a special institution for recourse

for victims of (real or perceived) racial discrimination.

TWO MONTHS LEADING TO THE MARCH

In June 2003, Government brought a closure to the sugarcane producing

state-owned Caroni (1975) Ltd. By September 2003, the traumatic effects of being

unemployed was bearing down on the 9,000 displaced workers, the majority of whom

were Indians. Yet, as Guardian (Oct 23, 2003) editorial writer pointed out,

there was no sustained programme in place for vulnerable groups, "single

mothers or Indians affected by the closure of Caroni (1975) Ltd." The Maha

Sabha also later contended that the Government did not respond to the

"distress call" of Hindus and Indians reeling from the impact of

social displacement (Maharaj, Parsuram 2004:10).

In August 2003, Prime Minister Manning indicated that HIV/AIDS education was

lacking in Trinidad, and the Caribbean as a whole. In his 2003/2004 National

Budget presentation on October 6, 2003, Manning revealed that his Government was

establishing a National AIDS Coordinating Committee, which was to be supported

by a loan of US $20 million from the World Bank. Little or no emphasis and

expenditure is being spent on social and health problems that particularly

afflict Indians like rural poverty, functional illiteracy, domestic violence,

diabetes, alcoholism and suicide (Rampersad 2003).

Early in August 2003, the Government began to organize a cultural contingent to

represent the country for the regional show-case, CARIFESTA V111, in Suriname.

Of the fifteen groups selected to be part of the organizing committee, only two

were Indian-based. All fifteen groups, except the organizing National Chutney

Foundation, were asked to select a representative to be among the 100-member

contingent traveling to Suriname. Cultural groups like The National Phagwa

Council were not invited and, therefore, the dholak [drum] - the national symbol

of Suriname - could not have played a significant role in country's

performances. It is needless to say that Indian cultural artistes and

performances were grossly underrepresented in multi-ethnic Suriname, which

hosted the show under the theme, "Many Cultures: The Essence of

Togetherness, the Spirit of the Caribbean."

The support for, and existence of, the Theology Department of the only state

University (UWI) in the country came under scrutiny from the Maha Sabha. The

Hindu organization charged that "the dispensation of theological studies

perpetuates discrimination and religious bias better suited to the Middle

Ages." It added that the Department provided priests and pastors with

theological degrees at the taxpayers' expense while the Hindu community has been

told over the years to provide its own funding to establish a Chair of Hindu

Studies at UWI (Maharaj, Parsuram 2003:10).

Connected to the Theology Department at UWI is the Trinity Cross as a national

symbol of honour in a multi-ethnic secular state. The supreme symbol is bestowed

by the President to an individual annually on Independence Day (August 31st) in

a country where there are followers of Orisha, Islam, Hindu, Baha'i, and Shouter

Baptist. The Maha Sabha argued that the "advocates of the Trinity Cross are

contemptuous of devotees who are not Christians. Moreover, the cross is a symbol

of European arrogance, and is an insult to some people who have suffered under

colonial domination" (Maharaj, Sat 2003: 22).

The Maha Sabha went on to link the issue of the Trinity Cross with

Afro-domination in employment in state institutions and agencies like Petrotrin

(oil company), The Central Bank, National Flour Mills, the Unit Trust

Corporation and CEPEP (road cleaners), and COSTAATT (Community College).

A spark burst into a racial fire when it was revealed that the Government wrote

in its Social-and-Economic-Policy-Framework-2004 document that it was seeking to

"establish targeted recruit programmes for male Trinidadians aged 17-24,

especially Afro-Trinidadian males" for COSTAATT. While one Minister

rushed to describe the paragraph as a printer's error, two others confirmed that

it was indeed part of Government's policy.

KIDNAPPINGS BEFORE OCTOBER 6TH

Trinidad, Guyana and the Dominican Republic have seen a rise in kidnappings for

ransom in the Caribbean that police believe to be a lucrative new business for

criminal gangs. At the end of March 2003, nine kidnappings were reported in

Trinidad with most of the victims being released relatively unharmed after

wealthy families paid as much as TT $5 million (US $830,000.) (Smith 2003). By

August 7, police sources disclosed that there were 33 victims for whom abductors

demanded a total of nearly TT $58 million (US $9,280,000.) of which only TT $2

(US $320,000) million were paid. By October 5, 2003, 39 people were reported

snatched for ransom (Marajh 2003:5), though non-police sources (e.g. Maharaj,

Parsuram 2003a:10) state that the number was about 170 victims.

Nevertheless, the 43-victim police figure reported by October 18, 2003

skyrocketed tiny Trinidad into international limelight as second only to

Colombia as the kidnapping capital of the world (Johnson 2003).

Indian commentators (e.g. Maharaj, Parsuram 2003a:10) noted that more than 80

percent of the kidnapped victims in Trinidad were Indians, particularly Hindus.

The Member of Parliament for San Juan/Barataria - a Muslim - observed, too, that

"the victims of kidnapping are Hindus and others with Hindu-sounding

names" (cited in Singh 2004). The charge was also made by UNC Opposition

leader Basdeo Panday that businessmen were being abducted not only because of

their wealth, but also because of their race. He noted that there were other

rich individuals in multi-ethnic Trinidad who were not, or hardy ever, captured

for ransom. At a public party meeting, Panday said: "Kidnapping is a racial

thing because the people of Goodwood Park and Westmoorings also have money, and

they are not kidnapped." He added that for some groups, kidnapping for

ransom of wealthy Indians may be "a way of distributing the wealth of the

country" (Homer 2003:7). In neighbouring Guyana, that ethnic crimes are far

worse. In a study done between February 2002 and February 2003, it was found

that all 18 kidnapped victims were Indians (GIHA Crime Report 2003:5).

The day of the protest marked 99 days since Darrell Chootoo went missing, and

there was the real fear that he was dead. Chootoo, 25 years old and a father of

two, was abducted by three armed men from his home in the presence of his

common-law wife and one-year-old daughter on the night of June 30. A ransom of

TT $300,000 (US $48,000) was demanded for his safe release.

On October 1, 2003, Shamshoon Mohammed, 33 years old, was abducted at an

aerobics classes and a TT $10 (US $1.6) million ransom was demanded for her safe

return. For three nights, vigils (described as a "wake without a

death") were kept at her Caroni home. On October 4, three days after her

abduction, news spread that she had escaped her snatchers. What is significant

about Shamshoon's abduction was that no ransom was paid for her release, and a

massive protest was ignited by scores of villagers with the support of members

of her Islamic faith.

On Friday October 3, 2003, residents of Caroni staged a fiery demonstration

against the high rate of uncontrolled kidnappings in the country. Shamshoon

Mohammed of Caroni was still in the kidnappers' custody, and prominent Muslims

led disgruntled and frustrated residents of her community to vent their feelings

in protest action. The main street was blocked with burning debris, and the

abandoned Caroni Post Office was burnt to the ground. "Muslims . sat

quietly in the middle of the road, [and] said they would not stay quiet after

juma [evening prayer], later that day" (Bisnath 2003:13). Police were

deployed but could not contain the rising anger of the residents and the

"aggressive behaviour from the Muslim community" (Bisnath 2003:13).

Though organized by Muslim leaders, the Caroni protest was cross-sectional and

multi-layered. As one journalist/scholar (Meighoo 2003:11) wrote:

The explosions on Friday in Harlem Village, Caroni was spontaneous (meaning,

without external cause, or self-generated, as in "spontaneous

combustion;" it does not mean instantaneous, or to catch "a vaps").

It spurred parallel self-organisation in Chaguanas on Monday.

One of the important aspects of the Caroni

protest was the visible defiance of the villagers. But the action seemed to mean

more. It seems a defiance of fear itself. One felt that the action, however

dangerous and out of control, demonstrated the sentiment, "We are not going

to live in fear anymore!" even as others feared - quite legitimately - the

implications and risks. It suggested an important new development that had to be

examined.

The protest action was inevitable, and it sent a clear message to the

Government. It set the pattern and fashioned the form for another demonstration

that was to take place in Chaguanas the following Monday.

To prevent and control a repeat of the anti-crime demonstration in Caroni, the

police and army came out in full force in Princess Town on Monday October 6,

2003. Members of the Crime Suppression Unit, and Guard and Emergency Branch were

waiting for action. Another solidarity protest had been organized by another

group of residents to shut down the town. All but one of the more-than 200

stores closed their doors, and taxi-drivers took the day off. The stores of

freed kidnap victims Tricia Teelucksingh-Suryadeva and Saran Kissoondath

remained closed, and business owners heeded the call to put up red flags and

ribbons as a sign of protest.

But although red-clad motorists honked their

horns, switched on their headlights and placed red ribbons on their vehicles to

highlight the problem, no one dared to participate in a planned illegal march to

the Princess Town Police Station.

The much-anticipated march was expected to start

around 9 am, but police thwarted the demonstrators, threatening to arrest anyone

who participated in the march. A Hindu priest sat on the sidewalk in the blazing

heat mediating, while police officers kept watch over demonstrators who

converged outside open stores holding red flags

(Sookraj 3003:3).

The protest was co-ordinated by a non-Indian, UNC Opposition Councillor Clifton

De Couteau, who said that the shutdown was "a community effort" (Asson

2003:5).

It is widely believed that a black Muslim group, the Jamaat al Muslimeen, is

behind the spate of kidnappings of mainly Hindu businessmen. Indeed, one

investigative reporter wrote:

The police have linked the Jamaat al Muslimeen to the continuing rise in violent

crime. Out-of-control criminal cells with connections to the Mucurapo mosque are

said to be behind the latest crime surge which has pushed murders and

kidnappings to an all-time high (Marajh 2003:5)

It is this militant group that had staged a failed coup d'état against an

elected Government in Trinidad in 1990 that made headlines around the world. It

was a bloody tragedy that left 31 people dead and 693 injured in the wake of

shootings and lootings. The Jamaat is active and growing, and is still feared by

locals and foreigners. It has powerful connections with, and influence on, the

ruling PNM which it helped to capture the Government in the last 2002 elections.

The belief that the Jamaat has links with al-Qaeda has prompted the British and

US Governments to be on the alert of possible terrorist threats to its people

and property in Trinidad. The country's natural gas tankers are easy explosive

target (Jacobs 2004).

THE OCTOBER 6TH ANTI-CRIME MARCH

During the Friday October 3, 2003 fiery anti-crime demonstration in Caroni, the

police were publicly chided for their apparent inability to control crime and

kidnapping in the country. The Acting Commissioner of Police, Everald Snaggs,

was not at all happy with public condemnations of his apparent incompetence. He

convened a two-hour meeting with his mainly Afro-Trinidadian executive officers,

and issued a public warning to groups planning illegal protest action to cease

and desist "or bear the full brunt of the law" (Cambridge 2003). He

said that he had information that "the intended activities of certain

persons . may disrupt the flow of normal public activities" on the next day

in Princess Town, Couva, and Bamboo Settlement. But despite the threat from the

Acting Commisioner, and cautious of it, residents of central Trinidad were

determined to make Monday October 6, 2003 a day of protest against crime and

police incompetence.

At 9.00am, the march started at Montrose Junction along the main road to the

bustling town of Chaguanas on a two-mile trek. It was organized by irate

businessmen and concerned residents in the area, and led by led by Chaguanas

Member of Parliament (MP) Manohar Ramsaran, Chaguanas Mayor Dr. Suruj Rambachan,

and members of the business community. The procession began with a small

interfaith service. Ramsaran advised marchers to walk in twos, so as not to

cause any disruptions, since, he said, he had information trouble-makers were in

their midst (Boodan 2003:3). Individuals discarded their placards out of

avoidance of possible police attack. The marchers, numbering more than 500 were

heading west and traveling in pairs on the sidewalk (Beharry 2003:3). An on-site

journalist (Boodan 2003:3) reported:

The marchers, led by Rambachan, were escorted by three policemen. As the crowd

made its way into Chaguanas, where all businesses had chained their doors for

the day, the gathering swelled with the influx of a number of concerned citizens

The otherwise peaceful march, which swelled to about 1,000 participants, turned

for the worst upon reaching the Chaguanas Market. Assistant Commissioner of

Police, Oswyn Allard, appeared on the scene and announced that the demonstration

had to end there. The command caused uproar among the large crowd.

Trinidad Guardian journalist Theron Boodan wrote:

At this point, Allard and a team of heavily-armed policemen approached the

crowd. He told the crowd the police would use force and arrest everyone if

the march continued.

Rambachan tried to calm the angry crow.

However, a plea to enter the Chaguanas Market car park fell on deaf ears, as the

crowd decided to push on.

At this point, several members of the public were

manhandled by the police, who succeeded in bringing order for only a short

while.

Political analyst Dr Kirk Meighoo who had gone to cover the march as a columnist

for the Express was one of the first to be arrested (Beharry 2003:3). He began

shouting from the back of the police van, "What is the charge? Why am I

being arrested?" A few metres from the Chaguanas Police Station, at around

10.30 am, Ramsaran had an argument with the police. Ramsaran was insisting that

it was a peaceful march without chants, bullhorns and placards. Allard

exclaimed, "I had enough!" and grabbed Ramsaran by his arm, pulled him

off the sidewalk, and pushed him into the van. Ramsaran's colleague, Hamza

Rafeeq, was also grabbed and tossed into the waiting police van and taken to the

station (Beharry 2003:3). This show of force, assault and arrest angered the

crowd even more. Allard then instructed his mainly-African officers to

form a chain with their batons to disperse the crowd. The protesters eventually

backed off and moved into the area used for driving tests by the Licensing

Authority (Boodan 2003:3).

One angry female eye-witness (Marajh 2003:13) wrote:

On more than one occasion, the police batoned female members of the public for

standing in the roadway; they pushed pedestrians and grabbed them by their shirt

necks.

As of today, this society now views Oswyn Allard

and acting Police Commissioner Everald Snaggs with immeasurable scorn, disdain

and hatred.

But yesterday's savagery and police thuggery must

surely have demonstrated tangibly what Mr. Manning means when he say that

"East Indians have nothing to fear," should they wish to come into the

PNM. .Monday, October 6, 2003 has now become a day of infamy.

Let it be known that as of now, instead of the

people cowering in fear, we are now driven by anger and rage at the sadistic

turn of events in Chaguanas.

I hope the world was watching as the police

brutalized the residents of Chaguanas and environs. Mercifully, the television

images showed how the partisan force demonstrated their loyalty to the PNM by

continuously barking orders at helpless Indians.

Dr. Meighoo was among the nine persons arrested. MP Rafeeq, Pundit Bisram

Siewdat, ASJA Imam Muakil Abdulah, Boysie Roy, Abdul Jabro, Jeewan Lutchman and

Bissondath Ramkissoon were charged for participating in a public march without

police permission. Ramsaran was charged with inciting people to take part in the

march. A national security helicopter flew overhead and the people gathered at

the police station waved to it. It circled the station twice and then

disappeared. After the charges were laid, around 2.30 pm, the men were escorted

to the nearby courthouse to appear before Magistrate Margaret Alert. Ramsaran

was not called to plead, and was granted bail in the sum of TT $650. (US $104.)

The others all pleaded not guilty, and were grated their own bail of $750. (US

$120.).

In a show of solidarity, most of the UNC MPs and senators went to the Chaguanas

Police Station. They had refused to attend the two-hour long presentation of the

TT $22.3 (US $3.6) billion Budget delivered by Prime Minister and Finance

Minister, Patrick Manning, that day. A team of attorneys and legal personnel

also showed up at the Chaguanas Police Station to give free assistance. Former

Education Minister and Attorney General, Kamla Persad-Bissesesar was manhandled

by a plainclothes police officer outside the Station, while attorney Anand

Ramlogan had to face an "arrogant, hostile and aggressive officer" (Ramoutar

2003). Opposition leader Basdeo Panday, who arrived later, said the Budget

presentation paled in comparison to the rights of people, and described the use

of force by the police on the streets of Chaguanas as "obscene."

Journalist Theron Boodan wrote: "Tears of joy and the applause of hundreds

of supporters of MPs Manohar Ramsaran (Chaguanas) and Hamza Rafeeq (Caroni

Central) filled the air near the Chaguanas courthouse yesterday, when the duo

was released on bail."

BEYOND POLITICS

There are those who even hold the view that the Opposition has been organizing

the spate of kidnappings of mainly-Indians in the country. Even if this theory

is true, it still does not exonerate the police for not identifying and

arresting the abductors. Critics and opponents of the march were quick to write

if off as an Opposition UNC politically-organised and -motivated form of

protest. However, investigative Newsday reporter Rhondor Dowlat (2003:8) wrote

that the October 6th 2003 march was a "solidarity walk" organized not

by politicians, but by the Chaguanas Businessmen and Women's Group in their

fight against crime and kidnapping. The fiery Friday Caroni march as well as the

Chaguanas street procession was a popular people's protest. Political scientist,

Dr Kirk Meighoo (2003:8) who was arrested in Chaguanas, wrote:

Frustration of villagers burst out like spontaneous combustion. It went

beyond politics. The UNC could not have organized that. The passion was too

strong. The villagers obviously were not concerned about the petty scoring of

points against the PNM, or the improbable task of trying to get the UNC into

Government (how could this be achieved with an election due in 2007?). The

defiance was a sign of confidence, although with many dangerous risks.

If the march was "political" at all, it was the attempt by politicians

to re-gain recognition and integrity by riding the back, and taking the lead, of

a popular protest movement that would have gained more potency without them. The

spirit of the march was neither sparked by the UNC nor was it directed by the

politicians. Opposition MP Hamza Rafeeq, for example, who was at the forefront

of the procession, is lackluster politician and a poor orator with a fixed smile

on his face, who can motivate no one.

Guardian columnist, Nirad Tewarie (2003:23), also wrote:

The people who were involved in the protest may or may not have been affiliated

with the UNC but, whether they were or not, they are still citizens who feel

that their concerns about the record-breaking murder rate and increase in

kidnappings are not being taken seriously by either the Government or the

police.

Participants of the march were angry frustrated people who had lost confidence

in the integrity and competence of the police and Prime Minister. They were

determined to make a public statement about an issue that threatened their very

life.

THE RIGHT OF PEOPLE TO PEACEFUL PROTEST

Every individual in Trinidad is entitled to all the rights and freedoms

enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Article 2 of the

Declaration states that a Government should not make any distinction of any kind

based on race, religion, or political affiliation in its treatment towards its

citizens. The Declaration sets out different kinds of rights and freedoms to

which human beings are entitled, one of which is the equal right of work in all

state departments and agencies. The Government in Trinidad has a responsibility

and duty to every person to provide security from physical harm, criminal acts,

kidnapping, and police assault. Article 20 of the Declaration also states that

everyone has the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and association. To

disregard this right is to show contempt for human rights which has resulted in

barbarous acts against people in other parts of the world. The right enshrined

in Article 5 could reasonably imply freedom from unlawful assault, arrest, and

many other forms of physical interference or restriction, including interference

with one's freedom of _expression (Robertson 1991).

The police physical interference, restriction, assault and arrest of

participants in the peaceful anti-crime procession in Chaguanas constitute a

violation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. In far-away New York, a

political analyst (Bisram 2003:33) wrote about the October 6, 2003 incident in

Trinidad:

The recent arrest of MPs and several other prominent individuals, and the

alleged beating and roughing-up of protesters in Chaguanas, infringe on

long-cherished basic democratic rights of the people.

A demonstration is a core fundamental right, as

long as it does not infringe on the rights and freedoms of others. It is part of

public action, which in turn is related to the formation of democratic public

opinion.

In democratic countries, people are free to

assemble, providing they are not violating the rights of others. So, unless the

two arrested MPs and demonstrators were violating other people's rights, for

example by impeding access to businesses, they should have been free to march

and assemble.

He argues that a police permit is usually sought for demonstrations only in

areas where there is limited public access, or where the would-be protesters

need police protection. Where a large demonstration is expected, a police

presence is advised to regulate the crowd and traffic.

Protest marches of a rowdy, high-risk nature were undertaken by

Afro-Trinidadians in support of the PNM in 2001, and the police did not assault

and arrest anyone as they did Chaguanas participants in 2003. PNM Legal Affairs

Minister, Camille Robinson Regis, and PNM Public Relations Officer, Rose Janiere,

led one such march and no one was arrested. The senior police officer on the

scene said that once the protesters kept moving, they were not breaking the law

(Tewarie 2003:23). A police permit was not obtained. Another "illegal"

march was led by Dr Selwyn Cudjoe, who is a PNM party campaigner and Director on

the Board of the Central Bank of Trinidad. In December 14, 2001, he led a march

towards the President's House to deliver a petition by hand in support of the

PNM in the 18-18 PNM-UNC electoral deadlock. Cudjoe did not obtain a police

permit, and more so, was more of a security threat since he was stepping into

the guarded property of the President of the Republic. Cudjoe and his followers

were neither stopped nor arrested. In response to the discriminatory assault and

arrests in Chaguanas, attorney-at-law, Anand Ramlogan, asked, "I want to

know where was Mr Oswyn Allard and all those police officers with guns when

Selwyn Cudjoe was marching? I want to know, is it going to be one baton for

Indians when they march in this country for their rights?" (Newsday Oct 7,

2003)

Opposition MP Manohar Ramsaran blamed Assistant Commissioner of Police (ACP),

Oswyn Allard, for the physical interference and restriction which caused the

chaos in Chaguanas. Ramsaran said, Allard "caused all the bacchanal."

He added that the march was "very peaceful until Allard arrived and

everything then turned ole mas[querade]." Manohar told a newspaper reporter

(Ramoutar 2003: 8 & 9):

You could say that it was a church march; it was quiet.

We did not use any bullhorn because police said

no to do it; we did try chanting, but because the crowd was about half-a-mile

long, the chanting faded quickly.

Some people had placards but the officers told us

that that was illegal, so we put them down; we were marching two by two and

cooperating with the police.

As I said, it was when Allard and company

arrived, the trouble started. The ACP started shouting that we should break up

the march immediately, and I looked at him wondering why he was carrying on so.

My cellular phone rang and I started to talk.

When I raised my head, I saw Dr. Meighoo in a police van, and I put away my

phone asking what was going on.

I heard Allard telling Dr. Rafeeq that he has 30

seconds to call off the march; I was not taking him on, so I suppose that's why

he spoke to Hamza, and I heard Hamza saying 30 seconds was too little to

disperse any crowd.

Exactly 30 seconds later, while we were

discussing it, Hamza and I were snatched and pulled into the police van.

Ramsaran said that during the first two hours in custody, they were

"treated very aggressively." They were not allowed to answer their

cellular phones, and the police treated them "very rough." One of the

organizers of the march, Sursatee Bharat, felt that the actions of the police

were "clear intimidation and abuse of power." She said: "This is

a non-political move [march]. This is residents of Chaguanas saying enough is

enough." (Newsday Oct 7, 2003)

A public UNC meeting was hastily summoned at the in Debe High School on the

night of the march on October 6, 2003. Dr. Hamza Rafeeq told the large crowd

that he realized for the first time that citizens' rights and freedoms were

being taken away from them. He said if persons were not allowed to show how they

felt about the crime situation in the country peacefully, they then had no other

alternative but to protest violently. Rafeeq added: "No struggle is too

great for freedom in this country, and under no circumstances would we allow our

people to be brutalized and just stand up and watch" (Ramoutar 2003b:20)

Political scientist and Express columnist, Dr Kirk Meighoo, detailed his

experience of being arrested without an explanation. As a member of the media,

he had gone to Chaguanas that day to observe and "get a first-hand account

of this historical event." While following the march, he (Meighoo 2003a:11)

wrote:

I was apprehended and put into

a police van. Mystified, I respectfully asked the officer whether I was being

arrested, and if so on what charges. I received no answer. I asked again,

"Sir, on what charges am I being held?" No answer. This continued for

five to ten minutes. I received no answer and the police van pulled off with two

Muslim brothers (of African descent) and me in the back.

I asked the policeman in the

van, "Sir, on what charges am I being held?" No answer. I asked again.

When I arrived at the police station, I asked, "May I ask on what charges I

am being held?" No answer. I asked, "In that case I would like to go

home. I will leave my name, number, and address if you would like to press

charges at a later time." But I was prevented from doing so.

Dr. Meighoo was arrested and detained without any immediate stated reason or

explanation. The usually-vocal Media Association of Trinidad and Tobago

(MATT) was noticeably silent. In the entire print media, it was only

fellow-Indian journalist Nirad Tewarie (2003:23) who raised the issue publicly

in his column. He saw the action of the police as an infringement on "the

constitutional rights as a citizen of Trinidad and Tobago." He said that,

as a journalist, he was prepared to defend his own rights and the rights of

others in such circumstances.

The large deployment of armed police officers at Chaguanas, and the assault they

inflicted upon the participants of the march was seen, by attorney Ramlogan, as

a "total show of intimidation" against target victims of crime and

kidnappings (Newsday Oct 7, 2003). One on-site reporter (Persad 2003:4) wrote

that the march "was progressing peacefully along the pavement, escorted by

three policemen," when ACP Oswyn Allard appeared and chaos broke loose. The

reporter captured the sentiments of participants and on-lookers:

"Like is a police state we have now,"

muttered a rain-soaked, well-known, middle-aged, bespectacled businessman .

"It looks like only criminals and police

have rights," a rotund retrenched female Caroni (1975) Limited worker

enjoined from the fringes, anger etched on her face. "But what is the

difference?" someone else interjected, "police and bandits same

blasted thing. Why Allard and them don't go and lock up the bandits and

kidnappers?"

"How they go lock up their friends?"

the emotional woman, hand on hips can cheek colour now matching her red jersey

with a rush of blood, blurted. "You ain't see they protesting them

bastards. You can't see whose side they on? Imagine they against we for

demonstrating against crime. They supporting the criminals then. Well, I never

see more."

Columnist Nirad Tewarie (2003:23) wrote in his Guardian column:

The arrest of 12 people, including two Opposition Members of Parliament, in

Chaguanas on October 6, is abhorrent, unjust and an attack on basic democratic

principles. It should be condemned by every person who believes in freedom of

speech and freedom of association regardless of creed, race or political

affiliation!

One female by-stander (Marajh 2003:13) was intense in her condemnation of the

police action on a day when the national budget was being presented in

Parliament:

And to think, those parliamentarians including those of East Indian decent sat

in the Parliament, indifferent to the brutality and breach of the human rights

taking place. All of them sat there pounding the table like fools.

After Monday, October 6, 2003, Mr. Manning has

shown clearly how the Police Service is indeed a force to be used against the

people. We now understand why kidnappings of Indians are being allowed to become

so fashionable. It is simply because the police do not care and have bought into

the Executives sinister agenda to terrorise their perceived political opponents

via criminal acts of one kind or another until they either succumb to political

indentureship, Vision 2020-style, or leave the country.

I say that as of Monday, October 6, 2003, this

nation's resolve has been strengthened. It is now abundantly clear to all and

sundry that the police are not on the side of the lawful and the decent, and are

prepared to beat, baton and manhandle citizens who oppose Mr. Manning.

The police have become a partisan army and are

now the enemy of the people and conversely the friend of the criminal. This

political directorate will pay dearly for the atrocity meted out in Chaguanas.

The Chaguanas march was historic in more ways than one. It took the limelight

over the Budget presentation in all the media networks. The police action also

found disfavour with Indian columnist Raffique Shah, who is a known pro-PNM and

anti-UNC commentator. Shah (2003:12) wrote:

Still, once the protesters were not blocking traffic or other people from using

the road, why arrest them? Personally, I have always found that particular law

to be in breach of people's fundamental rights, and downright offensive. A

people must always be entitled, as of right, to adopt such measures if they feel

aggrieved, or, as was the case here, if they feel Government is not being

proactive on an issue as serious as crime.

Express columnist Raoul Pantin (2003:12), too, would have condemned the police

assault and arrests. Pantin is usually not sympathetic to Indians or the UNC.

But he had written on the day before the march:

Every time someone is kidnapped in this country, the entire national community

should express its outrage and demonstrate in public to impress upon the

Government that it is not fulfilling one of its most basic responsibilities -

which is to provide the average citizen with a secure environment.

Of the all the condemnatory remarks made, it was that of Opposition leader

Basdeo Panday which really hit the nail on its head. The march and its outcome

had energized the 69-year old embattled leader. At the public UNC meeting at

Debe, Panday said that the PNM was using "the police as an instrument . to

discriminate against people." He added: "But people of this country

have taken as much as they can. People are saying enough is enough and are ready

to fight, ready to fight at all cost" (Persad 2003:4)

In neighbouring multi-ethnic Guyana, the police was used by the racist PNC

Government regime to intimidate and arrest people mainly of the opposition

party. The Guyanese security forces felt free to arrest Indians who had

criticized the Government, or had merely attended an opposition public meeting.

An atmosphere of pervasive repression overshadowed Guyana under the regime of

President Burnham. Basic human rights, including racial discrimination, had been

extensively denied to people perceived as communal or ideological enemies (Premdas

1989:40). There are many indications that Trinidad, under the PNM, is fast

becoming like Guyana under the PNC. Non-Indian journalist Kim Johnson, pointed

out in October 2003 that Indians in Trinidad were afraid. He wrote, "Maybe

there fears are justified; maybe not, but to them it is as real as the rain, and

has to be dealt with as such."

THE AFTERMATH OF THE MARCH

The police were successful in diffusing the anti-crime march in Chagaunas, but

the protestors felt victorious. They showed that they were not passive lambs

waiting to be snatched by criminals and kidnappers. Their strength lay in

solidarity and visibility. They were willing to fight police incompetence,

Government negligence, ethnic discrimination and racial violence with their bare

hands in a silent procession in the main street. The march was held at a time

when Hindus in Tunapuna, St Augustine, Carlsen Field, Orange Valley, California,

Felicity, Carapichaima, Tarouba, Cedar Hill, Matilda, Debe, Siparia and Rio

Claro were preparing to stage the annual enactment of Rameela. The

open-air drama recounted the legend of the kidnapping of Lord Rama's wife, Sita,

and the eventual defeat of the wicked abductor Ravana. Rama did not cower in

fear or hide in refuge. He fought a bloody and fierce battle, and severed all

ten of Ravana's heads with a single arrow.

The October 6th 2003 march, and police assaults and arrests, made frontpage

headline news. PNM Government Junior Minister of Finance, Conrad Enill, admitted

in his contribution to the Budget debate that crime was a serious problem in the

society. Enill said:

At this point we cannot be oblivious of the escalating crime situation in this

county. Our citizens are under siege. We must and shall respond to ensure the

safety of our communities

(Lord 2003:7).

He said Government had developed an 11-point crime and justice programme to

provide additional resources for the safety and security of all citizens. The

Prime Minister could not have ignored the public spectacle of 1,000 Indians on a

main street protesting about being targeted victims of crime and kidnapping. He

was obviously embarrassed about the attack on his apparent incompetence and

inaction. But instead of directing his rage at criminals, he spent more time

rebuking the protestors. Prime Minister Manning warned, ". the Government

wished to make it absolutely clear that we will not tolerate acts of civil

disobedience and will enforce the laws of the country rigidly and

fearlessly." He saw the silent demonstration as an act of

"lawlessness" organized by "persons who wish to disrupt the

society" (Persad 3003:4).

Manning's warnings were more than the mere utter of words. He announced that

"the Riot Squad will be the subject of review, and shall be provided with

the most modern equipment now used in the countries around the world" (Persad

2003:4). He also promoted a Commanding Officer of the Trinidad and Tobago

Regiment, Colonel Peter Joseph, to the position of a Brigadier. Joseph was

mandated to establish a Special Crime Fighting Unit. A few weeks after the

Chaguanas march, Manning also appointed Martin Joseph as the new Minister of

National Security. And as if to teach Indians a lesson for the audacity to

demonstrate against his Government, Manning also announced higher financial

allocations for CPEP, URP and NHA projects, of which mainly Afro-Trinidadian PNM

supporters were the main beneficiaries.

The rate of kidnappings continued after the Chaguanas march but declined during

the following months. The protest was not without reward; it had effected

substantial positive changes. Still, in October 2003, updated travel advisories

from the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom warned tourists about

"significant" increases in murder, violent crimes, and kidnappings for

ransom. Britain, in particular, warned its visiting citizens of an "an

increased terrorist threat" in Trinidad (Heeralal 2003:9). As an excuse for

his incompetence and inefficiency in apprehending criminals, acting Police

Commissioner Everald Snaggs said that "a lot of kidnappings in Trinidad and

Tobago were not genuine" (Cambridge 2003a:3). Prime Minister Manning was to

echo the excuse of Snaggs by stating to a live foreign audience in the United

States that many of the kidnappings in Trinidad were family feuds, drug paybacks

and staged events. While a few cases were indeed so, the vast majority were

indeed genuine criminal acts of terror and violence.

In the meantime, wealthy Indians are leaving the country with their human and

financial capital to invest abroad. Those who choose to stay are re-locating

their children to safer grounds in United States and Canada. There are those who

are applying for asylum and refugee status outside of Trinidad. Businessmen and

professionals have imposed a night-time self-curfew, and hire private bodyguards

and armed escorts. And like the spectators who watch the drama of Ramleela, they

hope and pray for the eventual destruction of King Ravana, and the triumph of

the rising sun over the evil of darkness stalking the land.

NOTES

It was reported that "CEPEP has been making millionaires out of small-time

contractors in the very first year of [the PNM] Government - funded business

venture. About 100 of these contractors have been pocketing hefty monthly

salaries over the past 18 months since the inception of the controversial URP-style

small business venture. In this time, Government had doled out over $73 million

to the programme" (Mohammed 2003:8)

In February 2004, the Minister of Agriculture, Land and Marine Resources,

Jarrette Narine stated that Caroni Lands will not be distributed to former

workers of the old sugar factory. He said, "Distributing small parcels of

land for housing and small-scale farming cannot be economically viable to

agriculture, and will not benefit our country in any way." Although the

original plan was to disburse small portions of the 12,000 acres of Caroni land

to retrenched workers, Narine said the Ministry had given this matter serious

re-consideration (Mokool 2004:4).

REFERENCES

Asson, Cecily

2003 "Princess Town revolts

against kidnapping wave on Monday." TNT Mirror October 3. Page 5.

2004

Bisnath, Elizabeth

2003

"Curb Crime or else! TNT Mirror October 5. Page 13.

Bisram, Vishnu

2003 "People have a right to protest." Guardian

October 22. Page 33.

Boodan, Adrian

2003 "Disorder in Central

again." Guardian October 7. Page 3.

Cambridge, Ucill

2003

"Police chief warns illegal marchers." Express October 6. Page 3.

Cambridge, Ucill

2003a "Many kidnappings bogus, says CoP." Sunday Express

November 1.

Page 3.

Dowlat, Rhondor

2003 "UNC MPs Ramsaran and Rafeq arrested and

charged." Newsday October 7. Page 8.

GIHA (Guyana Indian Heritage Association)

2003 Indians Betrayed: Black on Indian Violence, Government's

Denial and Inaction. Georgetown.

Guardian Opinion Editorial

2003

"Careless political move by Gov." Guardian October 29. Page 30.

Heeralal, Darryl

2003

"Tourists warned about crime in T&T." Express October 29. Page 9.

Homer, Louis B.

2003

"Bas plans more 'heat'." Express October 8. Page 7.

Jacobs, Donna

2004 "Trinidad's Ties to Terrorism." Ottawa Citizen.

January 24.

Johnson, Kim

2003

"Fear is the key." Sunday Guardian October 19, 2003.

Lord, Richard

2003

"Citizens under siege." Express October 22. Page 7.

Maharaja, Parsuram

2004

"The Best Justice." Newsday February 10. Page 10.

Maharaj, Parsuram

2003

"UWI failing Theology." Newsday October 7. Page 10.

Maharaj, Parsuram

2003 a

"Kidnapping." Trinidad Newsday. October 14. Page 10.

Maharaj, Sat

2003 "Trinity Cross must go." Guardian September 10.

Page 22.

Marajh, Camini,

2003

"Cops link Jamaat to crime wave." Express October 5. Page 5.

Marajh, Lystra

2003

"Manning's day of infamy." Express October 19. Page 13

Newsday "

2003

"Bacchanal in Chaguanas." October 7, 2003. Page 9.

Meighoo, Kirk

2003 "Beyond party agendas."

Express October 8. Page 11.

Meighoo, Kirk

2003a "Fear and folly." Express October 12. Page 11.

Mokool, Marsha

2004 "Gov't rethinks Caroni land distribution plan."

Guardian February 29. Page 4.

Mohammed, Sasha

2003 "Hefty handouts for CEPEP contractors."

Guardian February 2. Page 8.

Pantin, Raoul 2003

2003 "Make more noise." Express October 5. Page 12.

Paul Gordon Lauren

1988 Power and Prejudice: The Politics and Diplomacy of

Racial. Discrimination. Boulder: Westview Prss.

Persad, Siewdath

2003 "Oh, what a day .." TNT Mirror October 10. Page

4.

Premdas, Ralph

1989 "Political Power, Race and Human Rights in the

Caribbean: The Guyana Case." Plural Societies July edition. Pages

1-40.

Robertson, Mike, editor

1991 Human Rights for South Africans. Cape Town: Oxford

University Press.

Ramoutar, Harold

2003 "The Chaguanas march against crime turned

sour." TNT Mirror October 10. Pages 8&9.

Ramoutar, Harold

2003 a "Kamla

manhandled by cops." TNT Mirror October 10. Page 14.

Ramoutar, Harold 2003

2003b "Panday: We'll fight the PNM, regardless of cost." TnT

Mirror. October 10. Page 20.

Rampersad, Kris

2003 "Suicide Central." Guardian August 24. Page 32.

Singh, D.H.

2004 PRESS RELEASE. Hindu Writers Forum, Chaguanas.

January 1.

Shah, Raffique

2003 "Police action backfires on PM." Express

October 12. Page 12.

Smith, Mike

2003 "Gangs turn to kidnapping in Trinidad and other

Caribbean nations." Associated Press. March 30.

Sookraj Radhica

2003

"Cops thwart illegal march." Guardian October 7. Page 6.

Tewarie, Nirad

2003

"Tread Carefully, Mr. Policeman." Guardian October 18. Page 23.